An Investigation of "Nobody's Business" ・゚✧

Originally posted May 4, 2021 on tumblr. Readapted January 9, 2024. I was shocked how, less than three years later, most links were defunct. I've updated them, though I'm not confident these will fare better. As is such, extensive screencaps and source-citing follow this post. I don't want to lose more documentation.

It’s always a fun day when a song you thought was a cheery bluegrass number has its background in homosexual Harlem culture and its origin in Jamaican folk music.

So. My backstory. This morning I had a song stuck in my head I was singing around to myself, a catchy, upbeat, lighthearted ditty where the singer brags he lives life as he wants it, that it’s nobody’s business what he chooses to do. Since I’m a bluegrass-doused Flatt & Scruggs slut, I’d first come across the song from the band’s live recordings; sidemen and comedic duo Jake and Josh (real names English and Burkett, but that pairing doesn’t flow off the tongue) would take center stage to sing novelty songs, this being one of their most popular and common. After bragging off their carefree, independent lifestyle, the boys remember their relation to bandleaders Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs...

Now Earl says, “Boys, let’s leave at eight,”

And Flatt says, “No, that’s too late.”

(Nobody’s business what I do!)

And we all think, “Well, what the heck”

...but they’re the guys that signs our checks,a

So I guess it’s their business what I do!

[awkward laugh] Ha! Ha! Ha! Ha!

No matter how many times I’ve found their song performed, be it radio transcriptions, amateur concert tape recordings, or the Flatt & Scruggs TV Show, I get a kick out of it. Jake and Josh are one of my favorite parts of the act; I perk up when it’s their turn to perform duos; there’s an infectious happiness as two close friends sing harmony and the band energetically improvises on a rarer part of their repertoire. And there’s something hilarious about two men bragging about independent lives... only to realize, at the end, that they do have obligations and they’re not off the responsibility hook. Their own cockiness turns them into fools.

If you’d like to check it out, here’s one version from the TV show, complete with Scruggs nearly messing up his intro (to everyone’s fiendish delight), flashy fiddle and banjo moments, and bandmates laughing at their own humor.

Now obviously I knew Flatt & Scruggs didn’t write or buy the song, that it originated elsewhere, and that Jake and Josh, in referring to themselves, altered the final stanza to get an audience laugh.

But see to it my surprise when I began researching, and caught early blues versions of the lyrics and realized it’s oft a darker song about cocaine and drunkards murdering wives. The version I’d known was an aberration. As I explored other versions, I was listening to major bluegrass performers play it. I was in Appalachia. I was teleported to Jamaica. I was visiting Harlem.

And then it got gay.

It’s common in the early American recording industry to see blues songs cross over to the hillbilly (now called country) genre. It especially makes sense when you consider the artificial, record-company-induced delineation between “Black” blues and “white” country that didn’t reflect the full nature of what laypeople played. Rural black musicians played string band music, too, and there was constant borrowing, sharing, stealing, teaching, and adapting of musical ideas across racial lines both directions. It would take a separate post to talk about the yikes racism issues top to bottom, too, in the early music industry, and how that impacted who played (and got recorded for) what.

The 1920s brought in a big boom of vaudeville blues / classical female blues, a genre which combined traditional folk blues with urban theatre, and where Black women took center stage and sold successful records. This early commercial blues was filled with independent women stars. It’s from a number of these awesome ladies that we find the first recordings of Ain’t Nobody’s Business. The song received its record debut with Anna Meyers and the Original Memphis Five, recorded October 19, 1922 as Tain’t Nobody’s Biz-ness If I Do and released December on 78 rpm record Pathé Actuelle 020870.

I wasn’t surprised to find how different this song was from the hillbilly versions I’ve listened to. Folk song permutations do be like that. But if you’re not familiar with the folk world, a rather different-feeling melody, smooth but confident vocal crooning, and accompaniment with free-flowing piano and horns could make you think this was a different Nobody’s Business altogether. The lyrics of Anna Meyer’s version likewise have little in common with what I’d known. Because these words are so interesting, socially complex, and brazen, I’m going to share a close variation as sung by the great Bessie Smith April 26, 1923, whose Columbia A3898 version may be one of the most well-known:

There ain’t nothin’ I can do, nor nothin’ I can say

That folks don’t criticize me

But I’m going to do just as I want to anyway,

And I don’t care if you all despise me!

If I should take a notion

To jump into the ocean,

Tain’t nobody’s business if I do, do, do!

If I go to church on Sunday,

Then just shimmy down on Monday,

Tain’t nobody’s business if I do, if I do!

If my friend ain’t got no money,

And I say, “Take all mine, honey,”

Tain’t nobody’s business if I do, do, do, do!

If I give him my last nickel,

And it leaves me in a pickle,

Tain’t nobody’s business if I do, if I do!

There, I’d rather my man was hittin’ me

Than to jump right up and quittin’ me,

Tain’t nobody’s business if I do, do, do, do!

I swear I won’t call no copper

If I’m beat up by my papa,

Tain’t nobody’s business if I do, if I do!

Where these lyrics came from, in part, turned out to be Porter Grainger (1891 − 1955) and Everett Robbins (1898 − 1926).

Everett Robbins was a pianist, bandleader, and composer who was born in Muskogee, OK and moved to Chicago in 1916. He studied at the American Conservatory of Music, led his own bands, made piano rolls for Capitol Roll and Record Company, and recorded as a pianist with Mamie Smith’s Jazz Hounds (yeehaw! I know that group!). He is most known for Ain’t Nobody’s Business, which he co-wrote with Grainger in 1922. To my shock, I learned Robbins died at age 27.

Grainger was a prolific pianist, songwriter, playwright, and music publisher who was born in Kentucky, lived in Chicago, came to New York City in 1920, and settled in Harlem by 1924. He worked as an accompanist for many female blues singers, and two of his songs became blues standards. The other one, outside of Tain’t Nobody’s Business if I Do, is One is Dying Crapshooter’s Blues from 1927.

Given as Tain’t Nobody’s Business is a blues standard, I’m sheepish I didn’t know about its blues side, but I can dive to curious depth now. Grainger was a musician who modified folk material into his work, as with this song. [1] [2] [3] Then he integrated Harlem culture and a homosexual subtext into it; in fact there has been a 2011 documentary (I need to watch still) and a 2019 New York Festival of Song program named after this specific piece of music to explore Harlem gay culture. Grainger was queer, and many of the women performers lesbians or bisexual.

A blog entry from the New York Festival of Song discusses this. It’s worth reading the full article, btw:

Grainger’s personal life is more reminiscent of the blues women of the era. As the 1920s show dancer Maude Russell Rutherford, nearing 100 recalled, “I guess we were bisexual, that’s what you would call it today.” Another source claimed that all the great show singers were gay or bisexual: Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith, Alberta Hunter, Ethel Waters, Josephine Baker, all of them. The men in their professional lives, such as producers, were sexually demanding but showed no tenderness, and the showgirls roomed together. They risked being mocked as “bulldaggers,” but lesbianism was so common in that era it was almost accepted: for gay men, it was far, far worse.

And as a New York Times article brings up:

Conceived by Steven Blier, the festival’s artistic director, working with Elliott Hurwitt, a historian of early blues and jazz, the program offered music from the Harlem underground, including works by Billy Strayhorn and Grainger, as well as songs popularized by Bessie Smith, Alberta Hunter, Ethel Waters, Gladys Bentley and Ma Rainey — all of whom had, to different degrees, same-sex inclinations and involvements, even if some were married during portions of their lives…

Grainger’s “He Just Don’t Appeal to Me,” performed with disarming earnestness by Mr. Austin, was especially revealing. Though his lover has appealing “he-man ways” and is “good as he could be,” Mr. Austin sang, he just “ain’t got what I need.” Here was a song from the underground not just reveling in gay love but also suggesting the subtleties of attraction.

Going to church by day and a club by night was common for Harlem residents, as a verse in the final song on the program, Grainger’s “Tain’t Nobody’s Business If I Do” (performed by everyone) made clear:

If I go to church on Sunday

Then just shimmy down on Monday

Tain’t nobody’s business if I do

So while the lyrics of Tain’t Nobody’s Business may be subtler than other songs by Grainger and other composers and performers, its background coincides with early twentieth century Harlem queer culture.

One of the first recordings of Tain’t Nobody’s Business If I Do to veer into a debatably-country-ish side was recorded August 30, 1928 by Frank Stokes (1877 or 1888 − 1955) and released as Victor V-38500. Frank Stokes was a Black country blues singer from Memphis who’s often considered to be the father of the Memphis blues guitar style. I admit this recording sounds more “familiar” to me—I recognized the melody from the guitar intro—but it also aurally bridges the “gap” between versions like Bessie Smith versus Jake and Josh.

There’s one version that precedes Stokes that’s clearly part of the hillbilly genre and recorded by white performers. Warren Caplinger’s Cumberland Mountain Entertainers recorded February 1928 on Brunswick 224. It’s an upbeat, raucous string band performance, one with the same melody and chorus that you hear in the 1960s Jake and Josh performance from Flatt & Scruggs I showed you. There’s no mistaking these are the same song.

I was also interested to hear the 1935 recording by Riley Puckett (1894 − 1946). In fact it was Puckett’s record that accidentally started me on this research deep-dive; I was reading a chapter on him in a bluegrass book I bought, decided to do some YouTube listening, picked Nobody’s Business because I recognized the title, and then launched out of my chair when I heard a familiar melody but darker lyrics than anticipated.

I’m well-familiar with Riley Puckett from my hillbilly genre interests. He’s an important guitarist in the early country world. Blinded as a child, Puckett began learning banjo and guitar in his teenaged years, and began performing in fiddler’s conventions as early as 1916. He performed on WSB radio by 1922 with The Home Town Boys String Band with members including Clayton McMichen, and on March 7-8, 1924 worked with fiddler Gid Tanner to record Columbia’s first records in the nascent commercial hillbilly music industry. In 1926, musicians including Gid Tanner, Clayton McMichen, and Riley Puckett were brought together to form an influential old-time string band, the Skillet-Lickers (a band who’s caught enough of my interest I own several of their records).

What’s awesome about Puckett’s record (and the Cumberland Mountain Entertainers), now that I’ve listened to even more variations of this tune, is that the melody is clearly what Jake and Josh use, complete with their chorus, and some of the lyrics they use are similar. In the thematically mild, family-friendly Flatt & Scruggs performance, Josh Graves sings:

My wife drives a Cadillac

I walk the railroad tracks

(Nobody’s business what I do!)

She drives a limousine

I buy the gasoline

(Nobody’s business what I do!)

But you can see where their lyrics got derived from past aural folk traditions given recordings like Puckett’s version, where he sings:She drives a Cadillac

And that’s where she makes her jack

Oh boy, that’s where my money goes

That’s where my money goes,

Buying my baby clothes

That’s my business if I do

We can also compare with the Cumberland Mountain Entertainers, where several verses go:That’s where my money goes

To buy my sweet baby clothes

Nobody’s business if I do

She runs a Ford machine

I buy the gasoline

Nobody’s business if I do

She rides the Cadillac

Oh boy, she makes the jack

Nobody’s business if she do

But at the same time, Puckett and the Cumberland Mountain Entertainers both use stanzas more thematically evocative of what you'd hear in classical female blues music.

So altogether, you can feel that folk connectedness, even as melodies or words may vary. And as you can imagine, going through even more versions, you’ll find many instances in which the song narrator might admit to many different infractions, from drinking, gambling, morphine, cocaine, women, and murder… but exactly how it goes gets varied up. I don’t have time to cover everything, so I hope you get the idea of how American variations will differ. It’s almost hysterical that the version I heard first was the most mild, given the themes that many other variants present.

More well-known American performers and versions exist. Title variants include Ain’t No Tellin’, Cocaine Done Killed My Baby, Champagne Don’t Hurt Me Baby, It’s Nobody’s Business But My Own, It Ain’t Nobody’s Business, and It Ain’t Nobody’s Business What I Do. One version that gets repeatedly mentioned in sources is from Jimmy Witherspoon, so I feel obligated to mention this wonderful performance in brief: in 1947 Witherspoon revived the song so successfully it stayed on the Billboard race records charts for 34 weeks and was inducted into the Blues Foundation Hall of Fame in 2011.

However, there is one more IMPORTANT angle of this song’s origin that needs to be covered: Jamaican origin. [1] [2] [3] Listen to this.

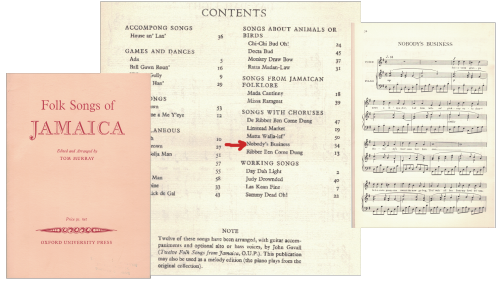

I wish I could find more concrete information regarding the Jamaican background of this song or speak to Jamaicans who know this information personally. Alas, I have various internet sites available to me right now and limited free time, not an entire physical library or an airplane. I did, however, find scanned images from Tom Murray’s collection Folk Songs of Jamaica that includes Nobody’s Business. It’s mentioned by various authentic societies, organizations, and performers, too, like the Jamaican Folk Singers:

Stories of the man-woman dynamic, love and gossip dominated the second movement. Yuh Tell a Lie, Woman a Heavy load, Fanny, 500 Feet a Board and Nobody’s Business were among the selections that were used to convey the themes in this segment to great effect. The addition of drama and choreography just added to the choreography.

It’s not hard to find versions of Nobody’s Business by Jamaican musicians, especially folk-oriented Jamaican musicians, but it's represented in many genres. [1] [2] [3]

As makes sense given the physical distance between the USA and Jamaica, I’m observing Jamaican versions can have noticeably different lyrics than any of the USA versions I’ve peeped into. However, the chorus has obvious relation to the USA chorus. It looks like the classical female blues arrangements in Harlem are the ones that diverged more from source material than the early hillbilly genre performers. I imagine that Jamaica is where the song began at all. Please please please note that I’m postulating with incomplete information, and that this entire post is written by an amateur, but a Black background for this song, transported to the United States through the slave trade, to be performed by Southerners of various races, rural Blacks, and African-Americans like Porter Grainger who used the folk origin for urban performance would make sense. Albeit from a questionable site, what I believe are notes from singer Dr. Marie McMarrow, discussing Jamaican folk music, might confirm this:

Nobody’s Business – Whatever you do in life is your own business.

Slave communities were built on philosophical council. The song “Nobody’s Business but Me Own” gives reassurance that people really ought to mind their own business.

What’s also enjoyable is that this song has entered the classical world through composer Peter Ashbourne, a leading classical Jamaican musician born in 1950 and living today. Nobody’s Business (But My Own) is part of Ashbourne’s Collection of 5 Songs for Soprano & Piano; it has been performed as part of Tulsa’s Greenwood Overcomes program which showcased Black composers, and where the site clearly states, “Based on a Traditional Jamaican Folk Song.” As Ashbourne expands:

Ashbourne shared that his compositions were encouraged by the nagging of his very good friend, soprano Dawn-Marie Virtue-James. “[She] asked me to ‘arrange a few folk songs for her in 1983; I immediately said yes, certainly, put this request on my bucket list, and forgot about it. It took another two years of her nagging, but I finally scored Banyan Tree, Water Come A Mi Eye, and Nobody’s Business for a recital she was having in 1986.” Over the next year, he also scored Fi Mi Love and Long Time Gal at her behest. “I am now glad that Dawn-Marie insisted I work on those folk songs,” he said.

Thus, today, Nobody’s Business is simultaneously a well-remembered Jamaican folk song, a Harlem blues standard framed in Black queer culture, a modern classical operatic work, and a country music song that’s been recorded since early 1920s and 30s hillbilly music and the later bluegrass scene.